American politics has given us many examples of inauthentic nonapologies in recent years. Yet Rep. Ted Yoho’s cringe-worthy attempt to apologize to Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez offers a fresh reminder of what not to do after calling your co-worker “crazy” and “f—ing bitch” — namely, go through the motions of an apology without an ounce of self-reflection or an attempt at maturity or personal growth.

Thankfully most of us are not in such dire circumstances when we mess up on the job. Our transgressions are less likely to involve lobbing desultory expletives at our colleagues and more likely to be well-intentioned but ultimately thoughtless snafus that can happen during major societal shifts. Errors will be made. So apologize we must.

To help you out the next time you royally step in it, our facilitators and coaches at Fringe PD have combined legacy research and modern experience to offer some enduring advice for apologizing effectively.

Sticks and Stones

One thing is true for any apology, whether on the House floor or in the 3rd-floor restroom: Apologizing poorly can sometimes cause more damage than not apologizing at all. That’s because a bad apology can add new layers to the original pain, and the tough circumstances at hand can reveal people’s true values.

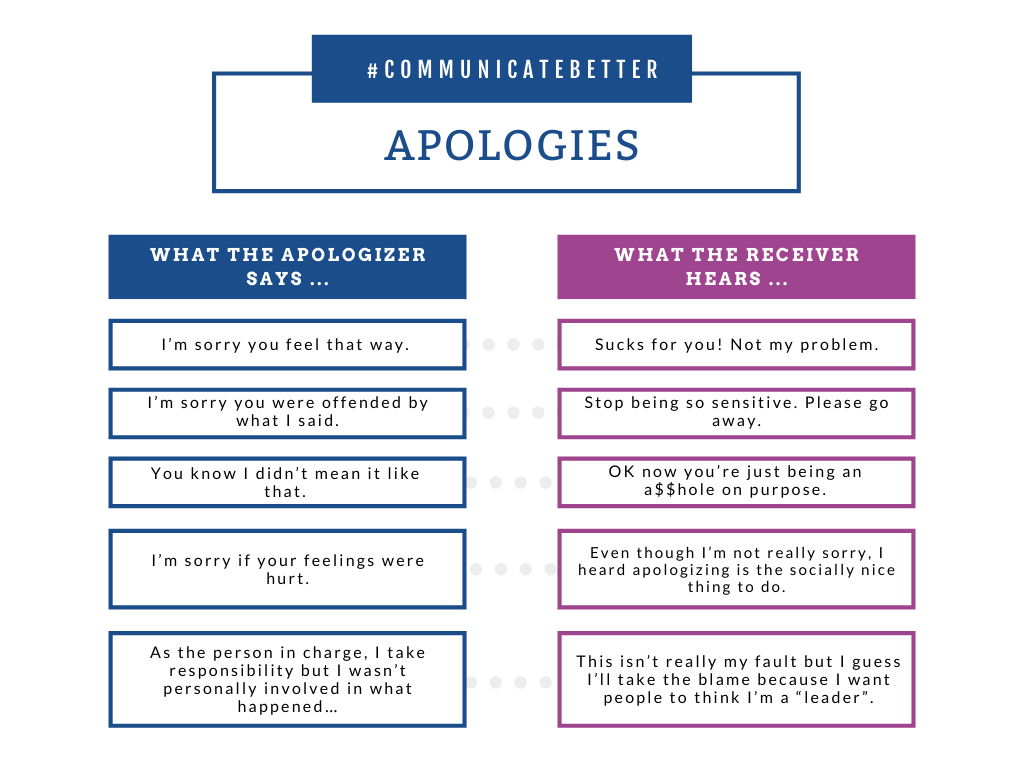

The biggest indicator of a bad apology is bad word choice. And as we’ve discussed at length elsewhere, successful communications doesn’t depend as much on the message delivered as the message received. Check out the table below for a comparison of what an apologizer says versus what the receiver hears. Then look in the C-SPAN archives for endless examples …

The bottom line is that someone else’s hurt is non-negotiable. An apologizer’s attempts to justify their actions, deflect ownership, or identify silver linings all deliver the message that the other person’s hurt isn’t fully legitimate. It also is a self-protection mechanism that continues to prioritize the apologizer’s interests over the receiver’s needs. If an apology is ultimately self-interested, then it isn’t much of an apology at all.

Don’ts and Do’s

Beyond language, tone and context can make a big difference in how well an apology is received. Here are some don’ts and do’s to keep in mind when you’re apologizing:

- Don’t be fake. Surface-level apologies might make you feel better — checking off a task on your ethical to-do list — but they don’t fix anything to move a relationship forward. If at the end of an apology, everyone goes back to their desks and pretends nothing happened, then something is wrong. Meaningful apologies are painful to deliver and sometimes just as painful to hear because they involve real work, accountability, and action in the form of behavioral change.

- Don’t sneak in “buts.” Notable psychologist Harriet Lerner teaches us that negative conjunctions of any form essentially “cancel” an apology. Even if the word “but” isn’t used verbatim, your disagreement is implied and reinforces the pain.

- Don’t deflect or retaliate. As evidenced by the backlash that blogger Rachel Hollis recently received from her fans when downplaying racist(?) plagiarism, passing off an error to someone else on your team can make you look petty and self-interested. Similarly, pointing out that other people — even the accuser — have committed similar transgressions in the past doesn’t help your case.

- Do believe the other person. If someone has the guts to tell you that they feel hurt/disappointed/discouraged by your behavior, don’t argue with them. Instead, think critically about the truth they’ve brought to your attention and what you could do differently going forward.

- Do stay chill. Some people panic and start over-apologizing. When you devolve into your own personal shame spiral, it often calls more attention to the incident — embarrassing the other person in the process. Effective apologies are not about you. Be sincere, be succinct, and move on.

- Do offer action. To demonstrate an interest in avoiding similar mistakes in the future, identify something you can do differently, and get the other person’s validation of that approach. “What do you think if I did X, Y, Z next time this happens?”

- Do expect to be uncomfortable. When you apologize, it should be uncomfortable. Period. We don’t like to sit with our own bad behavior, but this discomfort is where real progress is made.

It’s OK — and inevitable, really — to make a mistake that warrants an apology to someone who feels hurt. But you have to own it and fix it to move forward.

To hear more about best practices in communicating through conflict, subscribe to the alerts for our new Difficult Conversations series.